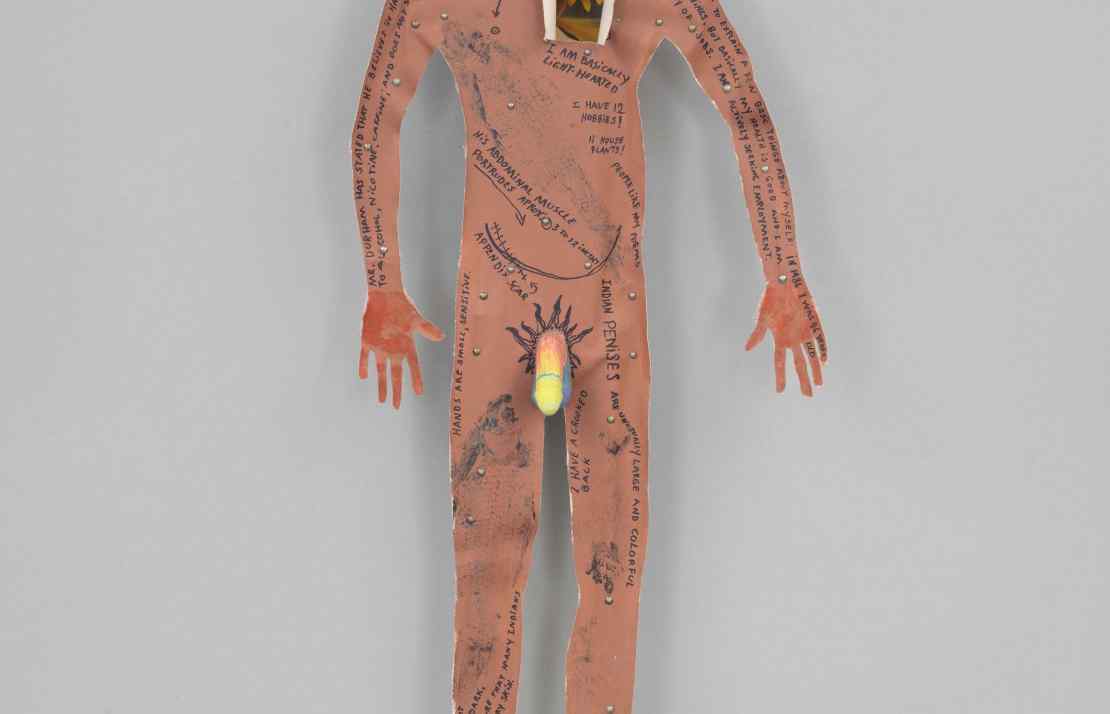

In 1986, when Jimmie Durham lay down on a piece of canvas and asked Maria Tereza Alves to trace his body’s outline, he had no idea of the controversy which would erupt 30 years later over the identification of that body, and the blood within. The occasion, the prestigious traveling retrospective Jimmie Durham. At the Center of the World curated by Anne Ellegood (2017-2018), provided the opportunity for a variety of artists, activists, and critics to voice long-held misgivings over his Cherokee heritage, citing everything from inconsistencies with his city of birth, to the fact he does not participate in pow-wows or ceremonies.

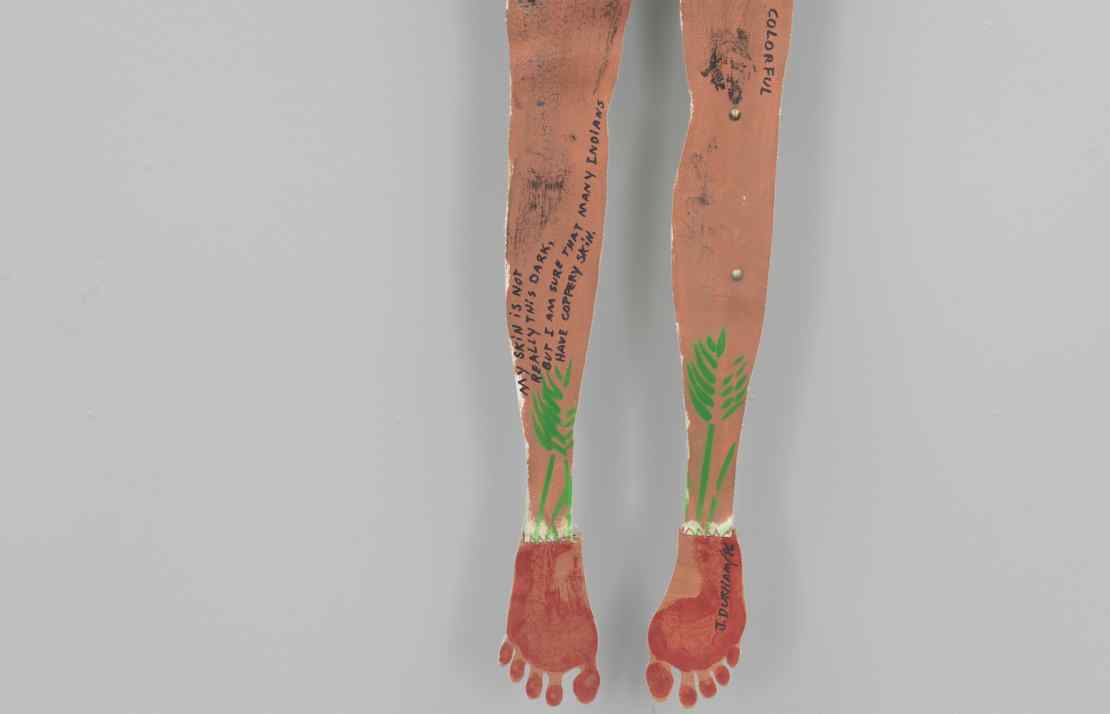

Yet, perhaps the Portrait presaged this brouhaha. The flattened surface mounted on scraps of wood, skull, and antler is fragmented, and disjointed — inscribed with competing statements and inconsistencies. Some are poignant, marked with longing, and the scars of judgement and expectations: “My skin is not really this dark, but I am sure many Indians have coppery skin.” Others, with hilarity, hint at the element of pure fantasy which pervades the colonial gaze: “Indian penises are extremely large and colourful.” A provisional bricolage of materials and meaning, Self-Portrait embodies the notion that identity is always constructed, fragmented, even contradictory1. And as the layers of shock, disavowal, and outrage accumulate with each panel and special journal issue, Durham remains silent on the subject. He always knew the non-Occidental body was the site of stereotypes, elisions, and fragmented beliefs. Indeed, as always, it reveals more about its viewers — and accusors — than the artist himself.

- 1. For instance, one of the markings on the work reads: “His abdominal muscle protrudes approx. 3 to 12 inches”.