The atlas of maps Milton-Park as Found was developed as part of my year-long graduating project at McGill University’s School of Architecture1. In this atlas, adopting a realist attitude, I explored the possibilities of seizing history “as found”; seeing everything that has accrued in our streetscapes, either recently or long ago, either beautifully or tritely, as forming a rich substrate from which we can design. The idea of drawing these maps emerged from an embedded understanding of the environment in which I lived in my own everyday reality throughout my studies at McGill: the neighbourhood of Milton-Park in Montreal.

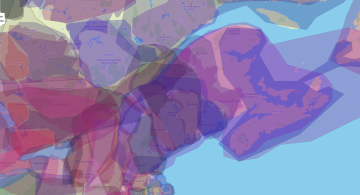

Milton-Park, often referred to affectionately as the “McGill Ghetto”, is located to the east of the main campus, between Mont-Royal to the North and downtown to the South. From its Victorian townhouses to its modernist high-rise, from its picturesque appearance to its inherent bricolage, and from its homogeneity to its diversity, Milton-Park is a “semi-historic” site that was shaped by a set of divergent social, morphological, and demographic changes. The resulting built fabric is at once coherent and messy, historical and absolutely contemporary.

The project sought the possibility of dwelling amongst this mess, culminating in an architectural proposition for the renovation and addition to the ballet school on Milton Street, Ballet Divertimento. Can the specific messiness of Milton-Park be seen as an identifiable form of order? The visual atlas Milton-Park as Found provided one of the mediums to answer that question.

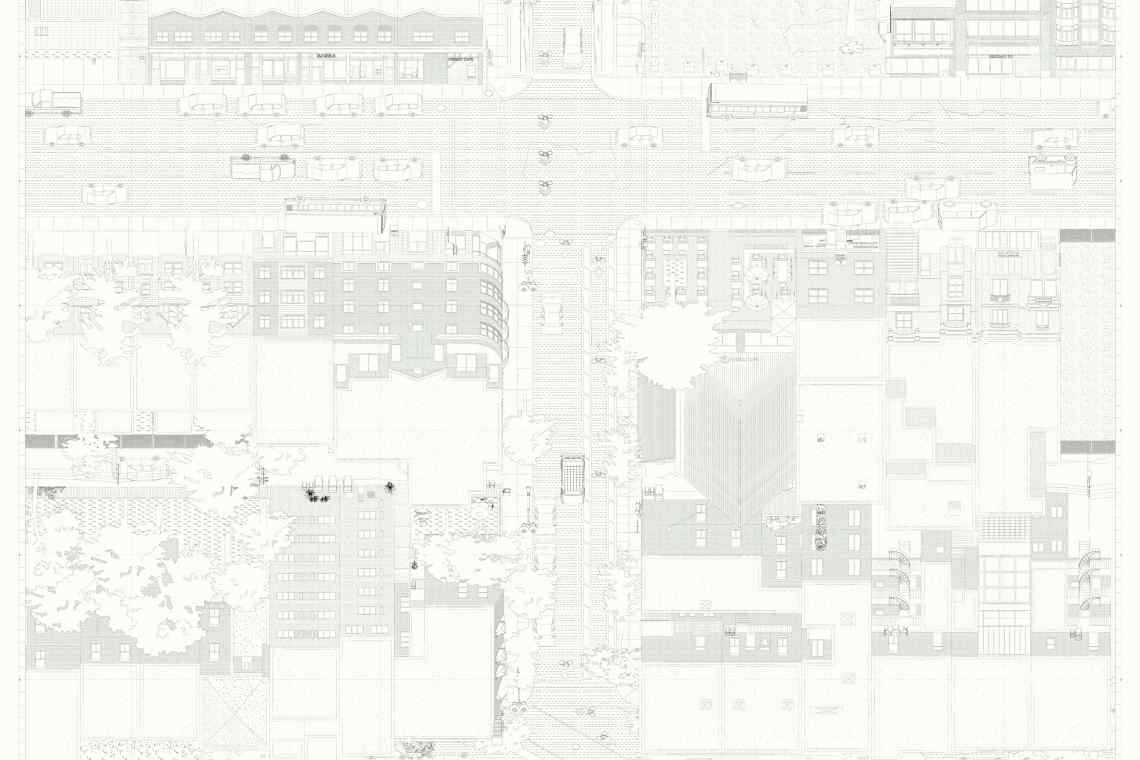

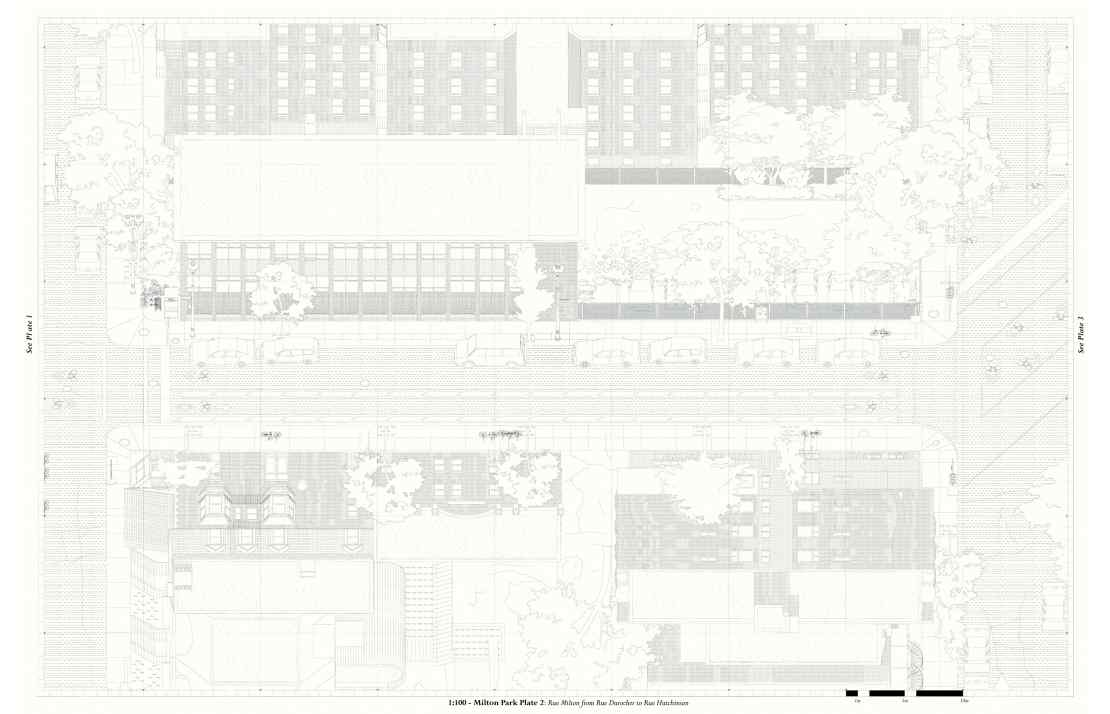

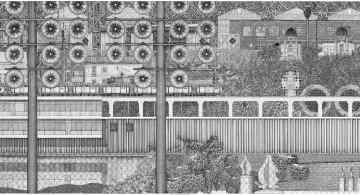

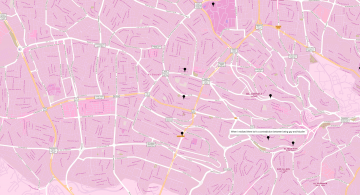

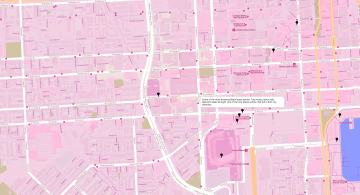

The maps focus narrowly on Milton Street, a major pedestrian axis that runs perpendicular to the dominant North-South axis, crossing all the residential streets of the neighborhood and revealing different moments and patterns, like a cross-section through its history. The four plates this axis creates map the Milton-Street blocks between Aylmer and Jeanne-Mance Streets. Looked at individually, the plates appear discrete and discontinuous. Even within each plate, the architectural patterns and languages are disorderly. But when seen all together, a special coherence emerges, as if the small-scale messiness was deliberate and designed as an ensemble. The fifth plate, which runs parallel to Park Avenue, shows how the eclectic constellation is interconnected through contiguity, and thus, through a shared temporality and spatiality.

The maps are drawn in a flat plan-oblique view, blurring the distinction between the architecture and its geographical reading. The maps do not record a static reality, but seek to interpret and stage it, as if walking through the streets. Acting as a mediator between reality and memory, the maps seek resemblance over identity — they seduce rather than tell — demonstrating how messiness can be attractive. They were drawn not by using lasers or 3D scanners, but by counting bricks and approximating distances and depths from photographs and older fire insurance maps. The result is imperfect and improvised, yet earnest and specific.

Milton-Park as Found aimed at a rigorous representational specificity, describing the neighbourhood objectively, but as it also appeared subjectively to the author. It captures the messy details and traces: windows, rooflines, lot divisions, cracks in the pavement, garbage bins, light poles, chairs, signage, electrical wires, and so on. The entire maps are drawn using the same line thickness, without hierarchy or contrast, seeking to dissolve disorder into evenness. The point is not to seek differences but relatedness, patterns, coherent forms of adjacencies and disruptive rhythms. Like a stage set with props, the maps invite the audience into a theatre of estrangement. Reading space up close and far away, digging into the details of the street whilst showing its entirety, and gaining focus on the images to soon lose it again, they lull the audience into imagining the everyday life that unfolds on Milton Street.

Some will remember the Milton-Park intersection, the bus stop and the student crowd, the lone bench, the terrain-vague blockaded by concrete blocks, and the homeless, the many homeless, indifferent and resigned. Some will remember the opposite side of the street: the coffee shop Milton B, the bad coffee, the pastiche architecture, the laptops and the outdoor patio. Some will remember the kink at the Milton-Hutchison intersection, the traffic lights, the swarm of cyclists waiting to turn left, and the chain link fence demarcating the parking lot for the ballet school with its overgrown plants. Some will remember the modernist ballet school itself, with the rhythmic stomps of the dancers and the classical rhythms of piano leaking out its windows. Some will remember the Bell phone booth at the Milton-Durocher intersection, used for many things except making phone calls. Some will remember the small bookstore The Word, with its musty yet civilized interior and its exterior windowsill, passersby peaking at the books laid out and others squeezing through impatient to get to McGill at the end of the street. As for me, what I’ll remember, always, along the messy Milton Street, are my many, many walks and strolls, sauntering with my camera over my back, trying to capture all of this lively disorder, only to end up with a binder full of too-static photographs.

- 1. I would like to thank prof. Martin Bressani, my advisor for this project, and Karlo Trost, for its constructive criticism and proofreading of this article.