On July 1st, 2015, a lion named Cecil was killed by an American big-game hunter in Zimbabwe and the internet roared in anger. Online commentators turned vicious, and in the days and weeks that followed I watched their rage become the story in itself. Facebook, Twitter, and many other social media sites of dissemination and display were overwhelmed by the global anger of their users. Articles — copiously illustrated with photographs — describing Cecil the lion and his tragic death were not only newsworthy, but unabashedly dominated the days’ events in both conventional online news forums, such as the BBC, and informal sites for news-sharing and trending, like Twitter. In story after story, the tale of Cecil was recycled — with slightly updated facts as they became available — through the various digital media networks that millions of people around the world check daily, hourly even. These sites of contact between digital news consumers and news makers algorithmically heave and sway as content is shaped by clicks and likes, and circulated in a seething online habitat of unpredictable feedback loops and nutrient cycling. For those of us on the connected side of the digital divide — active participants in a new media ecology (Hallas) that is informed as much by the corporate interests of "the image factory" (Frosh: 2) as by personal intention — Cecil’s story epitomizes the role that digital photography plays today in an increasingly networked global society.

The concept of "the network society," developed by sociologist Manuel Castells in the early days of the web, was premised on the belief that the digital transmission of data would fundamentally transform infrastructures of communication, employment, and governance, leading to a connected and information rich global society (Castells: xvii–xxxvi). Most radically, Castells identified the concept of "mass self-communication" as a new form of societal participatory communication which is "self-generated in content, self-directed in emission, and self-selected in reception1" (Castells: xxx.) As Martin Lister notes in his introduction to the 2013 edition of The Photographic Image in Digital Culture, the networked image — transient, fugitive, and potential — is "part of a larger reconfiguration of experience and mediation of the world by information technologies" (8). Today’s networked societies (to acknowledge that being connected globally does not mean the same thing for everyone) have successfully harnessed photography’s ubiquity (Rubinstein and Sluis), employing images across platforms both actively and passively, to offer consumers and makers of this massive visual culture — from professionals to amateurs and everyone in between — "the visual publicization of ordinary life in a ubiquitous photoscape" (Hand: 1). Today, as we stand on the brink of the Intelligent Web — sometimes called Web 3.0 — which is poised to anticipate our every interest and desire, the implication of mass self-communication takes on another layer of importance as the age-old question of media studies is revived: are we active participants in the new media revolution or only passive consumers shaped by forces beyond our control?

This article considers the presence of Cecil the Lion in the ubiquitous photoscape as a case study through which to measure the impact of participatory photographic culture on environmental activism and, more broadly, on the global environmental imaginary. The images created and circulated in response to Cecil the Lion’s death belong to a genre of photography that I have termed "eco-photography" (McManus). Eco-photography complicates the human understanding of the earth in balance and suggests a critical ecological or environmentalist reading of photography, whether it is through the subject of the image, its materiality, or its presentation and framing. I argue that eco-photography contributes to and reflects our growing perception of the environmental imaginary, an "un-unified" category of complementary and conflicting ideas, values, and practices that shape our global understanding of nature, ecology, and the environment (Buell: 3) — not to mention more publicly contentious scientific concepts, such as climate change, evolution, and the sixth extinction. As a discursive category based on continually shifting social and relational values, eco-photography must be understood to be one part of a larger environmental communication framework, which includes art and cultural representations, the media, public relations and activist strategies, and popular science communication (Cubitt).

Today’s post-photographic condition2 has radically expanded the creation and dissemination of eco-photography — indeed of all images —, shifting the practice of how images are employed by activists, artists, and concerned publics to communicate their messages of concern. Yet, eco-photography continues to be shaped by the convergence of old and new photographies and networks of dissemination. From traditional photojournalistic images of ecological disasters, to photographs documenting activist protests, to protests staged for the purpose of documentation — what Kevin DeLuca has termed "image-events" (DeLuca) — and still further to the participatory creation and dissemination of photo memes that generate their meaning through the image-making process: eco-photography employs technologies, tropes, and traditions of the past and present. We see this convergence clearly in the growing use of amateur images in news journalism and in the role of citizen photojournalism within alternative and community media sites (Allan; Forde; Tewksbury and Rittenberg). This paper argues that digital photography as manifest in the decentralized digital networks of our new global media ecology has played a central role in the renewal of an eco-photographic genre, appealing across platforms to viewers’ concerns about the global environment and thriving in “the culture of connectivity” (van Dijck).

Cecil the Lion as Post-photography: Always ’About-to-Die’

Cecil the Lion was not your everyday big cat. As a dominant male of a large pride living in the Hwange National Park, a tourist destination and wildlife preserve in the economically beleaguered and politically oppressive republic of Zimbabwe, Cecil was a popular local attraction and a major tourism money-maker for the park. With a striking black mane and the healthy physique of a well-fed male of his species, Cecil was also a classically photogenic animal who was unafraid of humans. He was a media superstar, a "charismatic" mammalian megafauna in the parlance of conservation science (Ducarme, Luque, and Courchamp, 2013). So when a white, privileged dentist from Minnesota named Walter J. Palmer, a hunter known for using bow and arrow to take down his prey, was named as Cecil’s killer on the web, things became emotional very quickly (Dearden). As the graphic details of the hunt were revealed, our rage — and I’ll include myself in the collective mindset — took on a more sinister cast as people on the web openly discussed whether Dr. Palmer did not deserve the very same treatment. Palmer’s office and home were targeted, with everything from death threats to children’s stuffed animals left at his door (Glenza, Kassam, and Smith). He soon went into hiding, although by early September 2015, he had returned to work at his dental office (Webber).

The case of Palmer’s hunt is disturbing in its particular details and also for how it exemplifies the larger legal and ethical problematics of the global trophy hunting industry. On the night of 1 July 2015, Cecil was lured from his sanctuary with poisoned meat, then shot with a crossbow. When he didn’t die quickly, Palmer and his handlers spent forty hours tracking Cecil through the bush, until Palmer finally caught up with him and shot him dead with a rifle. After the successful bag, Cecil was beheaded, skinned, and his corpse left to rot in the sun. Unbeknownst to Dr. Palmer and the men he hired to procure the lion, local hunting guide Theo Bronkhurst and land-owner Honest Ndlovu, Cecil was outfitted with a GPS tracking device, as part of a decade-long study conducted by the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit of Oxford University, which allowed researchers to track his last movements. As a result, the Zimbabwe Conservation Task Force found his body quickly, or what remained of it, and subsequently the two Zimbabwean men were charged in the local courts for "failing to prevent an illegal hunt" (Miller).

When the Zimbabwe Conservation Task Force named Dr. Palmer as the hunter responsible for his death, he promptly expressed regret that, "my pursuit of an activity I love and practice responsibly resulted in the taking of this lion" (DeLong). Palmer was especially disappointed to find out that Cecil was a local favourite and a celebrity on the nature-safari circuit. Dr. Palmer, who reportedly paid around 55,000 USD for the right, claimed that he had all the official permits required to commit the hunt (Dearden). Regardless of his defence of mens reus, claiming he had no intention to commit a crime, only the fact that Dr. Palmer was already back in the United States when he was named as Cecil’s killer allowed him to evade any legal consequences, as the Zimbabwean government shook its fist at the hunter from afar. Initial calls for Dr. Palmer’s extradition, which were ignored by the U.S. government, may have been little more than bluster on the part of Zimbabwean Environment Minister Oppah Muchinguri, who later announced in October 2015 that the American hunter’s paperwork had all been "in order" (Thornycroft, 2015). The ensuing international fracas between the African nation and the American hunter reinforced the global perception that wealthy Westerners can still get away with murder and that it was up to the court of public opinion to sanction the hunter.

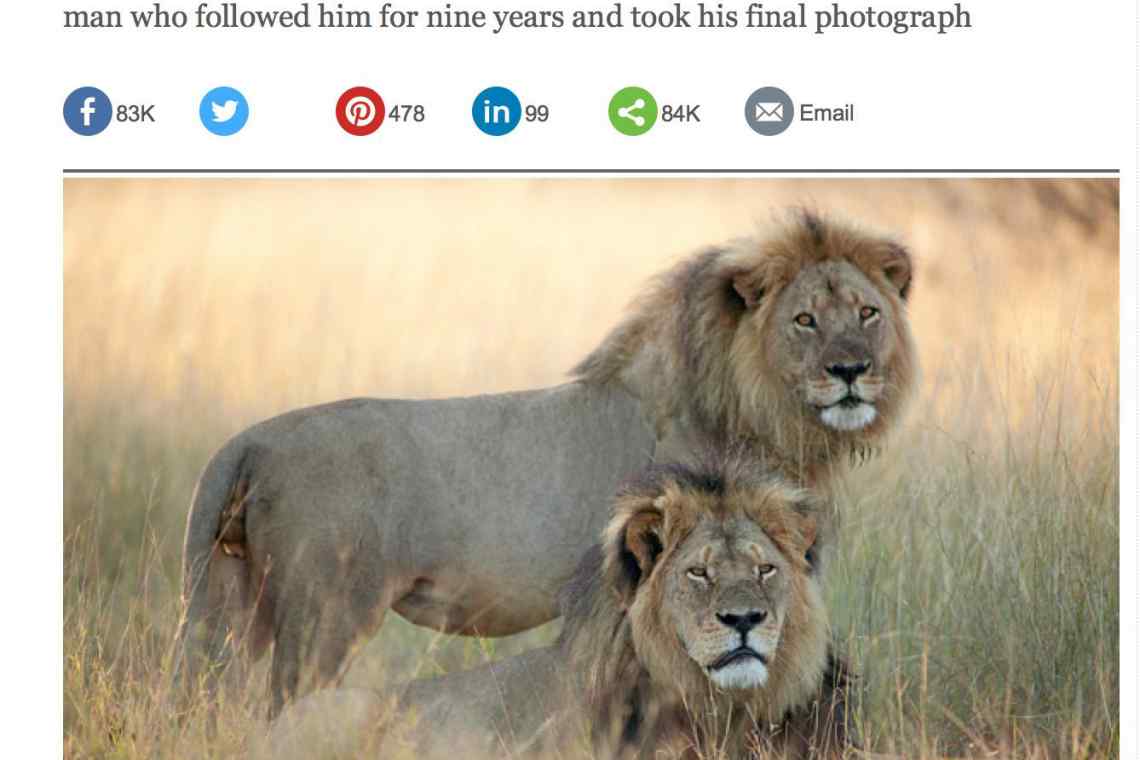

Most of the photographs that circulated following the news of Cecil’s death were typical of the event-driven photojournalism that remains the mainstay of the mass media. Gruesome images of Cecil did not surface. Instead, the online articles from mainstream news sources — the BBC, CBS, Reuters, Associated Press, etc. — all had similar stock images: Cecil looking majestic on the safari, Cecil drinking by the local watering hole, Cecil with one of his females or with his cubs, and Cecil with his coalition mate Jericho, one of the pride’s other males. Some of these images were credited to news sources but most seem to come from less official sources: images from travel agencies running safaris for profit or from scientists working on research projects based out of the reserve. In fact, the last known photo of Cecil, taken by Brent Staplekamp, a researcher at Hwange National Park, became a headline in itself (Alexander and Thornycroft).

These ’before’ photographs show Cecil as hale and hearty, offering the viewer an opportunity to mourn the loss of the majestic animal by imagining Cecil’s life as if it was ongoing. In his seminal Camera Lucida, Barthes locates the inherent pathos of the photographic medium — its sense of impending catastrophe — in the dialectical tension between the depicted past event, "this has been," and the viewer’s awareness of the subject’s future-past "this will be" (Barthes, 1980: 96). Cecil’s photographs — just like the pre-death portraits used to illustrate the subject of a newspaper obituary — are first and foremost emotional, showing the viewer what has been, while reminding us of what was to come, what is always to come to any living subject: death. In her research on the journalistic trope of ’about-to-die’ images, Barbie Zelizer writes that, "[c]entering not on the finality of death but on its possibility and, conversely, its impossibility, images of impending death allow journalism to remain open to the contingencies involved in the images that shape it" (24). Although Zelizer’s research focuses primarily on images in which death is metaphorically depicted, for example in the form of a gun or the dark pooling of a victim’s blood, I argue that the ’before’ images of Cecil at home in Hwange National Park function in a similarly affective way. By depicting a subject we know to be dead in his ’before’ state, the viewer is presented with the representation of what has been lost rather than the confirmation of death, the ’as if’ of the image is privileged over the ’as is’. The cognitive dissonance between image and text, between Cecil shown alive in his photographs and Cecil described as dead in words, reminds us of the power of photography to destroy our stable sense of linear time and order in the world. It also allows us to avoid the graphic and violent spectacle of death itself. By distancing ourselves from the discomfort of death’s representation, "the about-to-die photo also works as a vehicle of memory, becoming the central and often iconic image that stands in for complex and contested public events" (Zelizer: 26).

Cecil the Lion in a Social Media Ecology

The images that accompanied the stories of Cecil the Lion’s death were as important, if not more important, to the ongoing public responses than any of the written accounts. By offering an emotional focus for the event in a way that the facts did not — through the iconic image of nature’s inaccurately named King of the Jungle — readers, viewers, and commentators acted quickly to appropriate Cecil’s image for their objective, activist, or emotional re-telling of the story in the arena of social media. Yet rather than clearly divided along journalistic, professional, or personal boundaries of news telling and sharing, the photographs of Cecil the Lion, and the photographs produced to capture the public’s reaction to his death, became caught up in the ’participatory media culture’ of Web 2.0, which encourages us, in Henry Jenkins words, "to seek out new information and make connections across dispersed media content" (3). Jenkins’s concept of convergence is well illustrated by the participatory use of digital images related to Cecil the Lion’s death.

By using algorithmic search sites like Google Image and by employing Grab software to appropriate images from the web, participants gathered and circulated photographs relating to the event from personal and professional websites. As a result, Dr. Palmer’s smiling face circulated regularly, becoming a sinister reminder of Hannah Arendt’s provocative description of the banality of evil (Arendt). This amoral expression was epitomized by a circulating photo of Palmer, snatched from his dental practice’s official website, which was used in many online news articles juxtaposed alongside a ’before’ image of Cecil. Shot from the waist up, Palmer is shown smiling out at the viewer, wearing his dentist’s uniform of a white smock and professionally-whitened teeth. A boring image, slightly too magenta and a little blurry, meant to illustrate a biographical entry on a webpage, the image shows Palmer as a conventionally handsome, average middle-American white man. He looks very friendly and dependable, with a wide and ultra-white smile. In this image, Palmer’s crime, a culpability unfathomable to the perpetrator who cannot understand why his hobby is anyone’s business, comes across as unthinking, lazy, and divorced from the greater structural frameworks that allow and, indeed, justify the ongoing violence against animals in the wild. Placed beside a full body image of the glorious Cecil, walking towards the right of the frame —towards the photo of Palmer—one would be hard pressed to imagine a more innocuous pairing, should you not know the circumstances which brought these two photographic subjects together. United by violence, yet pictured from before the event, the paired image becomes a stand in for what we know has been and reminds us of the humdrum acceptance we would normally accord to such everyday occurrences of violence against animal bodies.

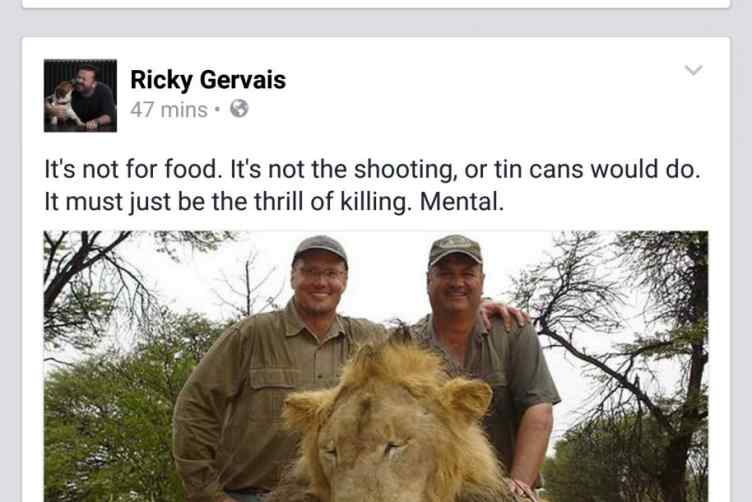

Many other kinds of images were used to represent different aspects of the story. Captures of tweets and discussion board debates often accompanied the articles of Cecil’s death as a way to produce the ’man on the street’ perspective so popular in journalism. Treated similarly to traditional photographs, these ’captures’ were themselves intertextual: photographs with captions and comments with their responses, were repurposed and treated like static digital images. Their reuse in this way gave a particular authority and stability of meaning to the images, at odds with the original purpose of the ephemeral message formats like Twitter and Facebook, meant to be constantly updated, commented upon, and altered through the sociality of the network. Instead, they reinforce the values of social connectivity in participatory culture, and thereby support the newsworthiness of the story, by emphasising how average citizens, experts, and celebrities alike saw the death of Cecil as deserving of commentary and circulation.

Another image trope that circulated widely on news and social media forums in response to Cecil’s death was the image of the trophy hunter posing with dead or dying prey. The ’trophy hunter self-portrait’ is not a new practice in photography: by the mid-19th hunters were actively using the camera to document their successes, particularly in the context colonial exploration and conquest (Ryan: 206). Once presented as symbols of frontier masculinity and sportsman etiquette (Brower: 44), today we could add to this cultural understanding of trophy photography (enlarged by the inclusion of women hunters) an elitist form of self-promotion in which the photograph both reinforces a hunter’s prowess and demonstrates their wealth and social status. These macabre ’selfies’ are popular in trophy hunting circles, perpetuated by the mass creation and dissemination of digital photographs online. While the bagging of exotic prey may require less skill than it once did, as hunted animals are frequently bred in captivity or sold at auction in a practice called "conservation hunting" (Phillip), it continues to rely on the deep pockets of participants: hunters frequently pay tens of thousands of dollars for the right to kill their prey. Following the naming of Cecil’s killer, the web was quick to identify a portrait of Dr. Palmer posing with not-Cecil but another lion he had killed. It didn’t stop there: Walter Palmer, a man of his technological time, apparently had uploaded many such images to a group Flickr site: soon we could see Palmer with a dead rhino, Palmer with a dead jaguar, Palmer with a dead ram. While these particular albums have since been removed from Flickr, you can still find examples of Palmer’s photographic hunting practice all over the web, as news agencies appropriated them to illustrate their stories. As well, many more images can be found on such hunting outfitter sites as Porcupine Creek Outfitters and Trophy Hunt America, where Palmer is shown posing with dead animals in multiple photographs (Sinclair). Many of the images included his weapon of choice, a powerful compound bow of a type popular with those hunters who feel like being more traditional in their deadly pursuits.

Cecil the Lion goes Memetic

The de-materialization of the photographic object by digital technologies, facilitated by the combination of the mobile phone camera and the web, has created a new photographic environment for all types of images, in addition to the standard media ecology made up of print, film, and television. As digital technologies improve, and more people, amateur and professional, gain access, the quality and quantity of these images continues to grow. Building on the viewer’s relationship to the real, to a desire for transparency in a complex world, and employing visual strategies to make global concerns more understandable, digital photography has created new forms of mass socio-political participation and self-communication. Of course, not all messages communicate and diffuse equally well, but when they do, they often go viral. The images of Cecil the Lion certainly did.

One example, which highlights the role of digital photography as a popular form of mass self-communication, is the photo-based meme. The term ’Meme’ was originally developed by Richard Dawkins to explain cultural change and adoption through evolution theory, attempting to encapsulate the relationship between biology, human behaviour, and socio-cultural practices (Dawkins). Communications scholar Limor Shifman, in her analysis of internet memes as a pervasive form of vernacular digital creativity, defines memes as "small pieces of cultural information that pass along from person to person, but gradually scale into a shared social phenomenon" (Shifman, 2014a: 18). According to Shifman, internet memes are marked by their compatibility with participatory culture: they are reproduced through social networks, actively repackaged by participants using methods of mimicry, remixing, and manipulation, and are assisted in their diffusion by socially-driven competition, ie. through ’clicks’, and ’likes’, and ’shares’ (Shifman, 2014a: 22). Internet memes can be video or still images, political engaged or purely silly, but they are always visually powerful and their transmission is shaped directly by viewers who choose to, or choose not to, spread the meme. As intertextual digital artefacts, Shifman argues that, "internet memes can be treated as (post)modern folklore, in which shared norms and values are constructed through cultural artefacts such as Photoshopped images or urban legends" (Shifman, 2014a: 15).

Internet memes are marked by their engagement in a form of ’do-it-yourself’ creativity, often inspired by practices or forms of image-making that have gone viral. In her analysis of the social media photography site Flickr, Susan Murray points out that users often develop communal aesthetic standards through group discussion and agreed collection criteria (Murray: 166.). Photo memes exist in a much less structured framework of online communities—anyone can make a photo meme and share it on any site, although they are particularly popular on forums like 4chan, Tumblr and Reddit — yet they somehow manage to repeat structural and aesthetic patterns across subjects and concerns (Shifman, 2014a: 132). This is function of the creation process employed by makers: photo meme producers utilize software programs such as Photoshop and online meme generators to quickly make new images from the old, reflecting and shaping the public response to an issue through transformation and recursive sampling. There are many types of photo memes but according to Shifman all are united by three key principles:

hypersignification — the code itself becomes the focus of attention; as prospective photography — photos are increasingly perceived as the raw material for their future incarnations; and as operative signs — textual categories that are designed as invitations for creative action. (Shifman, 2014b: 341.)

These concepts are not new to photography: we can recognize the roots of this form of analysis in the structuralist approach of Barthes’s early writings on photography, which questioned the signification of the photographic message (Barthes, 1977). Yet, unlike advertising and news images, which rhetorically naturalize their connotation procedures, photo-based memes rely heavily on the creator’s and the viewer’s awareness and acceptance of their digital logic.

Image macros are a type of photo-based meme that combine images and text to make a co-constitutive statement about current events, largely reflecting public opinions on socio-political or cultural issues. Often sarcastic, biting, goofy, punning, or bitter, image macros are typically characterized by white text overlaid upon an image, which functions to anchor the photo’s meaning, a twist on Stuart Hall’s classic relationship of news photograph to caption (Hall: 64). The image macro employs the photograph of a person or animal — LOLCats would be one exemplar of this phenomenon — who is either meant to typify a certain stock character, be it animal, socio-economic, ethnic, or political, or that of a celebrity who already embodies certain ideas or values in the mind of the viewer3. The crying lady image macro is a characteristic example, playing on the idea that women are emotionally unstable wrecks who will cry easily. Sometimes referred to as crying white lady, and combined with the phrase "first world problems," the stereotypes employed in image macros are often racist, classist, and/or gendered, demonstrating that the "socio-demographic background of meme creators (typically white, privileged young men)" (Shifman, 2014b: 348), strongly informs the creation, circulation, and interpretation of the images: a perfect example of how self-oriented content is shaped by emission (what sites are privileged for dissemination) and accessibility (who one’s friends and followers are) of memes. In the case of LOLCats, viewers and makers stereotype cats as interchangeable cute pets with human-like characteristics. LOLCats image macros don’t regularly engage in political commentary, but they do give viewers and makers a sense of belonging to an insider community: one that thinks cats are cute. Since cats are one of the most popular subjects on the web, this includes a lot of us (Williams). To appreciate LOLCats, viewers must have a familiarity with the internet dialect used in these image macros, giving them, in Shifman’s words, "the sweet scent of an inside joke" (2014a: 111).

The image macros that began to appear after the news of Cecil’s death went viral employed a number of characteristic qualities of the genre. Taking a pre-existing photograph from the web, often an image of Cecil from before his death, the maker would then add textual commentary and voila! Deeply hypersignified, these images are locked into a coded meaning informed by: majestic beauty, or carnivorous behaviour, or the tragedy of his fate at the hands of a small-town, small-minded schmuck. At times a twist is added, as in an image which shows a lion (not Cecil) licking his balls humorously paired with the phrase "moments before he was shot". Look, the image seems to say, Cecil is just like your own cat or dog. Other image macros mocked the viewer’s sympathy for the dead lion, suggesting that only naive and sentimental bleeding-hearts think lions are not dangerous predators. But soon, the hypersignification shifted towards, as Shifman puts it, "highlighting the constructed, or even staged, nature of mediated realities" (2014b: 344). Images began to appear that reflected other socio-political concerns of the day: in the U.S. the Black Lives Matter movement became embroiled with Cecil’s image, as did a scandal involving Planned Parenthood and the disposal of aborted foetuses by the organization. In reaction to the first wave of Cecil memes, from two different positions on the political spectrum, critical image macros appeared asking the same question: why do so many people get upset when one lion is killed?

The transformation of Cecil’s image from photojournalistic icon to an active image macro demonstrates that global animal rights, and particularly the rights of charismatic megafauna who live in the wild, like Cecil did, continue to resonate with people on and off the web. The viral success of Cecil’s image, which peaked and faded away just like any other internet meme (Coscia, 2013: n.p.) or news cycle, cannot be separated from the tensions inherent in his event-driven story. This type of event is all too familiar to those of us who worry about animal rights, biodiversity, and mass species extinction. Cecil’s story — about a beleaguered species living on a shrinking habitat too close to civilization and under siege by both locals, who should be protecting him, and by global elites, who use their wealth as both a lever and a weapon — made him a pointed focus for the many feelings of frustration and despair that accompany our current eco-historical moment. Many other types of eco-photographs have circulated recently on the web: images of oil-drenched sea birds, collected particles of plastic on shorelines, and the rolling black effluence emitted from the smokestacks of coal plants, to describe only a few. Yet, it was the specificity of Cecil’s death at the hand of an individual, along with his celebrity status, that successfully harnessed our current media technology as a tool of mass communication and censure. As participatory culture and post-photographic technologies reach more and more people, the web becomes a powerful tool for expressing moral outrage, anonymous attacks, and cyber-bullying. While Dr. Palmer will certainly be remembered for the media storm his actions precipitated, it is the image of Cecil that will be imagined and discussed when conversations in the public sphere turn towards the subject of wildlife trophy hunting. Thus the semiotic image-event becomes intertwined, inextricably contextual and inseparable from its larger environmental and technological moment.

Cecil the Lion as an Outlet for Environmental Concern

No images could ever begin to represent the complexity of trophy hunting in southern Africa: its role in many national economies, its importance in the micro-economics of small villages, nor its place in the history of post-colonial nation building across the continent (Onishi). Yet, by highlighting the conflicting passions and divergent positions in the contemporary global public debates about the value of animal life — sometimes heatedly addressed in contrast to the Black Lives Matter movement or to issues of global poverty (Ferreras) — these images help us to visualize and imagine humanity’s violent role in bringing about a major environmental crisis, an event that scientists have named the sixth mass extinction. African lions, unlike humans, are an endangered species and, although their current numbers are debated (twelve thousand? twenty thousand?), there is no question that they are drastically declining in numbers. A study from 2014 shows the western African lion as near extinction, with approximately two hundred and fifty documented animals (Howard). While southern African lions are less threatened, habitat loss, human-animal conflict, and the bush meat trade is putting pressure on the cats, which has led the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to call for their protection. The extinction of African lions by the end of the 21st century has been predicted (Platt).

The story of the death of one lion, a lion most of the world had never even heard of before the event of his death, offers viewers a focus for their general anxiety about the state of biodiversity on the planet. By extension, participants in the digitally networked global culture used the web as an outlet to express their sense of risk for the planet. Cecil the Lion’s story is emblematic of what Ulrich Beck has termed "the world risk society", a theory which explicates the role that risk and, more critically, the anticipation of risk plays in our global mediascape (Beck: 14–15). In our world risk society, participatory culture, including the creation and dissemination of images produced in response to events beyond one’s control, is a means for expressing our sense of helplessness in the face of overwhelming anxiety. While the activity of clicking and sharing an image, a story, a video, or an angry rant by the animal rights activist-celebrity Ricky Gervais may not appear to offer solutions, ’clictivism’, or ’slacktivism’ as it is sometimes called, offers viewers a tangible focus for their concern. As Alison G. Anderson writes:

[...] claims that deny the role of social media as a potent tool for bringing together diverse transnational networks and channelling protest in new and creative ways underestimate its potential. Furthermore exaggerated assertions about the power of social media to bring about social change tend to cast the media in a narrow deterministic lens. (Anderson: 33.)

Anderson argues persuasively that social media must be understood as intermeshed with the offline apparatus of environmental activism — as one of only many potential means of mobilizing support and action.

The case of Cecil the Lion is exemplary of eco-photography’s limited yet significant role in participatory culture. Cecil’s death and, we could argue cynically, his celebrity propelled the viral response to his questionably legal and certainly unethical killing. Yet the media event that followed has led to an outpouring of support for the ongoing research projects in Hwange National Park, run by the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit at the University of Oxford, which had received, as of 4 August 2015, over 500,000 British pounds from public donations (Press Association). By September 24th, 2015, over a million people had signed the online petition calling for "Justice for Cecil" in Zimbabwe (‘Petition: Demand Justice for Cecil the Lion, Killed in Zimbabwe!’). Several major airlines, sensing the mood, have agreed to stop transporting the pelts of the ’big five’ — buffalo, elephants, leopards, lions, and rhinoceros (Calamur, 2015). While many people expressed anger and even distaste at the global media’s preoccupation with one celebrity lion, and used image macros to register their frustration, Cecil’s death has made an impact on two important aspects of African wildlife conservation, drawing attention to the popularity of trophy hunting in the U.S., where the majority of foreign trophy hunters to Africa live, and highlighting the role of infrastructure and bureaucracy in facilitating this hobby. More generally, it brought large-scale public attention to the species extinction crisis, if only for a scant 15 minutes. Our participatory networked culture, if nothing else, offers tools for channelling the moral outrage of consumers — consumers of goods as well as images — into economic influence. What it doesn’t have much power to do is alter the fundamental unequal structures of our global environmental framework, which tacitly endorses the practice of trophy hunting of endangered and threatened animals as a justifiable cost, rather than addressing the underlying inequalities inherent in global capitalism which propagate the commodification of animal death.

The proliferation of eco-photography, even images of the most charismatic megafauna imaginable, cannot solve this complex and enmeshed state of affairs. Like about-to-die images, eco-photography is a morally ambiguous and socially significant type of image that has the potential to create opposing and multiple responses in viewers. Eco-photographs can offer a viewer the opportunity to pay attention, to learn, and to consider our rationalizations for today’s environmental policies and the resulting suffering. But our reaction to those images, whether we are emotionally and ethically impacted by photographs of environmental crisis or whether we are numbed into indifference or complicity, cannot be controlled or even reliably predicted. Eco-photography is a form of public photography that reflects and reinforces the values of existing public spheres, whether they be circulated through ’old’ media or new. Eco-photography’s success in the new media ecology, as exemplified by the ubiquitous and recursive usage of Cecil the Lion’s image, echoes the triumph of the network society, from its participatory, self-selecting, and self-directed logic of creation and consumption, and strongly illustrates the institutionalization of the culture of connectivity in the news media.

- 1. In this assertion, we can find the roots of today’s social media communication infrastructures, like Facebook or Reddit, in which users circulate content they make or appropriate while consuming content from other like-minded individuals. Today, with the ongoing rise of new digital communication technologies, most notably the smart phone and tablet and the many compatible software programs that help us connect, users/viewers/makers navigate through and migrate across multiple platforms and various media sites, both corporate and grassroots: their actions embody what Henry Jenkins has called "convergence culture" (3-4).

- 2. Post-photography — a contested term that is nevertheless used by many scholars and photographers as a shorthand for the changes to photographic visual culture brought about by digital technologies — has been defined by curator and photographer Joan Fontcuberta as a "visual ideology" for "[a new] era characterized by the mass production of images, endless accessibility, immateriality, and vertiginous dissemination" (Fontcuberta).

- 3. Keanu Reeves looking clueless as the titular character Ted from Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) is a common stock character.