In 2015 a new publication emerged from the Archive of Modern Conflict, the vast London-based private repository of vernacular photography. This publication, produced in collaboration with Erik Kessels, the Dutch vernacular photography collector and curator, was entitled Shining in Absence. It was in part collated to mark the death of another celebrated Dutch vernacular photography collector, Frido Troost, and to mark the acquisition of his entire collection by the Archive. Shining in Absence, like the exhibition of the same name it accompanied, contained no photographs, merely spaces where photographs used to be. If ‘found’ photographs — those usually vernacular images from family albums regularly apprehended for sale in junk shops and second-hand markets — already carry an elegiac quality, this project ramped up the mourning. In the Archive of Modern Conflict’s words, Shining in Absence is not only about the passing of a friend but also something much more major: it “is about the space left by the disappearance of photography as both an idea and as a material object.” (n.p.)

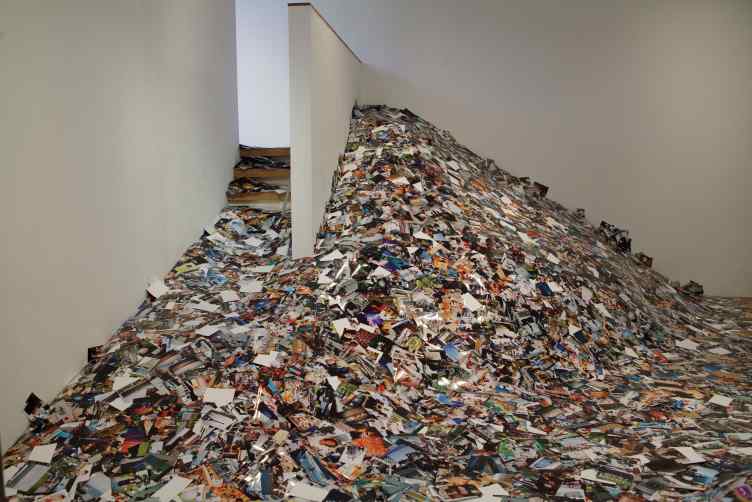

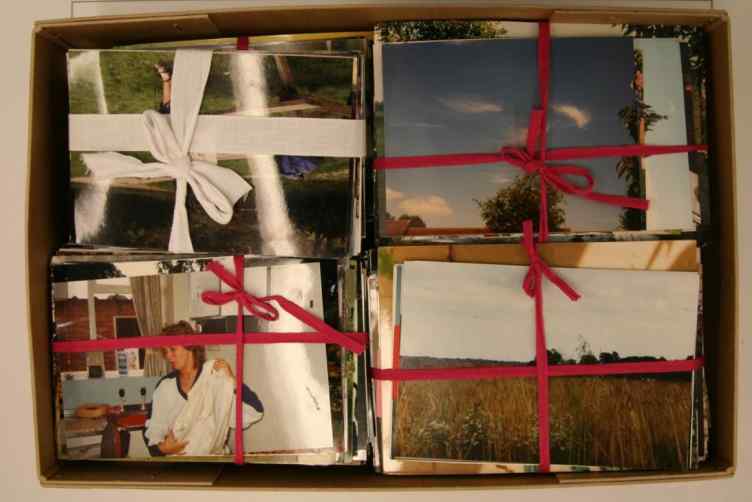

Kessels’s collecting, curating, and publishing commonly celebrates the beauty — and often the comedy — in personal and found photographs, albeit selections made and recontextualised through the idiosyncratic vision of the collector. Perhaps the exhibit that shows Kessels’s most tender affection for everyday analogue photography is his 2012 book and installation Album Beauty. In its iteration as an exhibition, miscellaneous and mostly anonymous school photographs, personal portraits, family collections, and more are piled up and scaled up for the viewer to revel in their material imperfections and their monumental glory. Popular photographic practice is also the subject of Kessels’s installation, 24 Hrs in Photos. Shown in various locations between 2011 and 2015, this exhibition is also marked by Kessels’ characteristic sense of the superlative, but here there is something more unsettling. Designed to illustrate digital photography’s new mass profusion, it shows the physical scale of photographs now available online. With approximately 1.4 million photos uploaded to Flickr per day by 2014 — to quote just one statistic that attempts to measure this new enormity — it has been estimated that to spend even one second viewing them all would take more than two weeks; if produced as standard photo prints, they would fill a room (Heikka and Rastenberger: 37). Printing roughly a day’s worth of photographs and filling a room is exactly what Kessels did. When compared with the gentle, singular pleasures of personal photographs in Album Beauty, 24 Hrs in Photos, comprised of around 950,000 prints piled high, the effect is surely to horrify. Kessels has frequently expressed his sadness at what he describes as the death of the traditional photograph album; the great undifferentiated hordes of digital photographs depicted in 24 Hrs in Photos, he seems to say, are what killed it off.

This article explores responses to photography’s 21st century massification, as a key aspect of the “condition” that curator Joan Fontcuberta (2015) has coined as “post-photographic”. Through an assessment of a variety of current forms — popular press opinion, leading-edge arts practice, and large-scale community projects — it offers a brief snapshot of the hopes and fears attached to photography en masse. By contextualising these responses within recent scholarly literature and also within historic instances of massification, this piece assesses and challenges the technologically determinist claims made for mass photography’s novelty. Finally, it offers some methodological reflections and suggestions for ways to understand mass photographic practice, old and new.

Post-photographic dystopias

Fontcuberta’s “intellectual adventure”(9), played out in his Post-photographic Condition book and exhibitions for the 2015 Mois de la Photo à Montréal, aims to define the characteristics that make photography so distinctive in the 21st century. Careful to acknowledge that his category of post-photography is not a movement, style or a historical period, Fontcuberta’s provocative and sometimes playful thesis is rich with new thinking and flamboyant ripostes to received wisdom. Yet, from the outset, he notes as his opening gambit: “We are bedevilled by an unprecedented glut of images.” (8.) In making such a statement, Fontcuberta expresses a conventional concern that there are too many photographs in the world, and the quantity is doing us no good.

In particular, in relation to what he calls photography’s “extraordinary accumulation”, Fontcuberta argues that “we find ourselves in an era in which images are comprehended through the idea of excess, an era in which we speak of the consequences of mass production as asphyxiation rather than emancipation”. The corollary of this “excess”, he notes, is “hypervisibility and universal voyeurism on the one hand, and blindness or insensitivity on the other” (12).Photographic volumes are variously described in his book as “cascades”, “explosions”, and “swollen rivers” (153, 11, 152).Their effects are assessed in pathological language: an “epidemic” that can result in vertigo (12). The dystopian view of photographic multiplication that Fontcuberta summarises – as well as reinforces – is a core anxiety about photography in the popular press of the 21st century.

Many articles in the national news media across the Western world wring their hands over the sheer quantities of photographs that are now taken and circulated. Emotive terms like ‘flood’ and ‘tumult’ are used to evoke a Biblical scale of practice and a sense of impending doom. To offer a quick sample from three major newspapers in the English-speaking world, a 2013 article in the British newspaper, The Guardian, entitled “The death of photography” asked, “Are camera phones destroying an art form?” Journalist Stuart Jeffries claimed, in his opening statement: “the world is now drowning in images.” (n.p.) Using a related metaphor, journalist James Estrin, writing for the New York Times in 2012, stated that we ignore at our peril, “the tsunami of vernacular photographs about to wash away everything in its path” (n.p.).In Canada’s The Globe and Mail, journalist and photographic judge Ian Brown gathered anxious professional photographers around him in 2013 to share their fears about the loss of photographic quality and meaning amidst a similarly described “technological deluge” of amateur practice. Amidst this rising tide of photographs, the practice of photography that generates the abundance of imagery is styled as pathologically persistent; “the visual equivalent of a hypodermic drip” When Brown asks, “why do we take them?” he concludes, “For the same reason addicts are addicted to anything: to kill the pain of awareness, the uncomfortable difficulty of actually seeing” (n.p.). Photography under these conditions is nothing more than “a form of neurotic masturbation, fuelled by an unstoppable sense of technological entitlement” (n.p.).

These apocalyptic claims could be dismissed as merely the inflated and attention-seeking language of click bait, if they did not resemble and thus perpetuate a longer and perhaps more respectable tradition of nihilistic writing about photography, seen most evidently in Susan Sontag’s (1979) work and her imitators. Claims have, of course, been forcibly made for the associations between photography and loss, pain and even death, by Roland Barthes’s development of an influential photographic thinking borne of bereavement in Camera Lucida (1981). While recent work has sought to undo the “cloying melancholia” that has been said to characterise “the post-Barthian era of photographic theory” (Green: 17), narratives of loss circulate in photographic writing, from photography’s supposedly inherent partnership with death to newer, but equally insistent, claims of the impending death of photography. Although post-photography as Fontcuberta describes it is not specifically a post-mortem of photography, it is still underpinned by a clear and present danger, as he and his co-authors imagine it: the loss of value and the loss of magic. In 21st-century image saturation, “the photograph loses the condition of exclusive exquisite object that it once enjoyed”, Fontcuberta argues (8). “Massification trivializes it. Extraordinary experiences… are overwhelmed by banal experiences.” (8.)

It is perhaps no surprise, given the shift of photography from a standalone industry to an aspect of a computational network (Risto and Frohlich; Kember), that fears about the declining value of photography mirror contemporaneous concerns about loss of expertise and quality in the internet age. A typical example of this approach — one of many — can be seen in journalist and “digital media entrepreneur” Andrew Keen’s book The Cult of the Amateur (2010). Keen mourns the transformation of “culture into cacophony” through “an avalanche of amateur content” that is styled as an “assault” that threatens “our values, economy, and ultimately innovation and creativity itself” (cover text).Even more broadly, and taking a longer view, debates about the growing access to and output of digital amateur photography also mirror historical concerns surveyed and ultimately dismissed in John Carey’s (1992) The Intellectuals and the Masses, which accounts for the scorn for the swarming rabble whose new access to literature threatened and consequently shaped the reactionary intellectual direction of literary elites between 1880 and 1939. With mass photography in the digital age, a similar elitist concern prevails.

The secure status of the singular vision of the narrow band of photographic heroes, so hard won through so many years of photography’s art historical valorisation, is made insecure — to continue the popular metaphor — by the opening of the photographic floodgates. Whereas once it was the case that large quantities of photographs might only be produced by small groups of professional practitioners, and the public domain of photography was necessarily limited to those with access to publication channels and their gate-keepers, with the radically expanded proliferation of popular photography in the 21st century and the newly accessible means for its public circulation, the regular anxieties expressed that there may now be too many photographs often reflect a concern that there are too many photographs of the wrong kind. The massification of photography is also sometimes linked to a more discomforting critique of photography by the masses.

Enormous numbers frequently accompany these worries and the round-up of millions, billions, and even trillions adds to the fear, not only about the mind-boggling scale of photographic practice, but also the repetitive sameness of its results. This can be seen in the articles mentioned above (and many more), including in The Globe and Mail’s title, “Humanity takes millions of photos every day. Why are most so forgettable?” (Brown: n.p.) Large numbers are seen to be necessarily leading to what the New York Times calls “the proliferation of mediocrity” (Estrin: n.p.). Each of the press articles cited roots its complaint in the ease of access, use, and circulation facilitated by the digital, but it may be that the problem is rooted more in the status of the amateur photographer, not her or his chosen technological means. For an example, we might look at the pre-digital grievances expressed by photographer and theorist Julian Stallabrass (1996), when he complained about the dearth of innovation or meaning in amateur photography in his book chapter “Sixty Billion Sunsets”, whose title is intended to communicate the mass-circulation of banality that is apparently inherent in the practice’s broad quantities.

In the post-photographic landscape — sometimes styled as photographic end times — artists root around, as if through the post-apocalyptic detritus, picking up the scraps left behind in the deluge. Robert Shore describes this kind of artistic method in his 2014 book Post-Photography: The Artist with a Camera. Here he describes a position whereby photographers “conclude that the world-out-there is so hyper-documented there’s no point taking your own pictures anymore”. He suggests that “a leading post-photographic strategy” is to glean from the abundant resources of the online environment in the guise of curator and editor (7). Other jeremiad authors whose work could fall under the rubric of the post-photographic include Fred Ritchin and his book After Photography. Ritchin has described how, in a world full of photographs, editors and curators are needed more than photographers. He suggests that rather than adding more images to “the masses of nearly undifferentiated content”, instead “it would be helpful if people began to more effectively filter some of the work already online” (115).Fontcuberta also focuses on “The post-photographic readiness” among artists “to make use of the overwhelming quantities of scale” made available by the expansion in mass practice (40).

Penelope Umbrico is a prominent artist whose work engages with what she describes as the “digital torrent” and “visual detritus” of photography online (Umbrico: n.p.). In her works, often based on a practice of scavenging from pre-existing image sources, she gathers together visual tropes, from sunsets on photo-sharing websites to photographs of televisions for sale on online auction sites. Frequently displayed in either vast grid formations or high-speed sequences, the cumulative effect is designed to communicate the overwhelming proliferation of the individually inconsequential, and to highlight the equivalent sameness of each attempt at individual communication. As she says of her own work, it is a comment on “the availability of everything” as well as the “contemporary conditions of detachment and isolation” (Umbrico: n.p.).

Umbrico featured in From Here On, the 2011 edition of French photography festival Les Rencontres d’Arles, which took photography in the context of the internet as its theme. Again curated by Fontcuberta, with Clément Chéroux, Erik Kessels, Martin Parr, and Joachim Schmid, Fontcuberta’s choice of post-photographic exhibitors for Mois de la Photo à Montréal thus reprises his long-standing interest in artists who explore the vast scale of digital imagery. Of the works he describes as post-photographic, he notes that many have a “catalogue aesthetic” and an “aesthetics of excess”. In Montreal in 2015, selected works by artists who utilise scale for their subject matter include Roy Arden’s The World as Will and Representation with its seemingly arbitrary selection of 28,144 internet-generated images, scrolling at dizzying speed in slideshow, or the 5000 images of bloggers in Christopher Baker’s Hello World!, displayed in a vast grid. While using different sources for different purposes, Umbrico’s, Arden’s, and Baker’s work is each designed to produce a bewildered, disoriented effect in the viewer — the visual equivalent of white noise or visual pollution.

Mass photographic potential

In my recent research (Pollen, 2012a; 2012b; 2013a; 2013b; 2016), I have been exploring current and historic photographic projects that feature a similar “catalogue aesthetic”, and which similarly engage with huge quantities of images, but the use that is made of these volumes is for a different agenda. They employ a different language from the art projects cited, which tend to take a critical, if not pessimistic, position. Rather than applying the terminology of addiction, disease or natural disasters, these mass photographic projects aim to harness the communication potential of mass image-making and operate in a much more optimistic frame: the terms that are preferred are inclusion, participation, and unity. The range of these projects is broad and their underlying purposes can be variously historical, sociological, charitable, or commercial, but together they represent a clustering of efforts to gather people together to capitalise upon a critical mass of networked camera ownership.

Often informed by the technological idealism that has also prompted a swath of popular publications that suggest that a newly networked world can tap into collective wisdom and problem solving (see, for example, Surowiecki), these kinds of projects see the massification of photography not as a bereavement for loss of quality and for loss of the material but as a means to realise a new world of utopian communication and togetherness. With a humanist ambition to bring nations or even the planet together, such projects have mass ambitions, and there are now a mass of them. In the last decade, projects that have attempted to harness the scale of the digital photograph have been extensive. Many focus on photography taken on a single day, whether to capture a symbolic moment of togetherness or to make an incision in the mass of photographs produced to take a snapshot survey of the world; often seen through amateur — and therefore, so the thinking goes — more authentic eyes. Variously organised by major charities, international news media, and photo sharing platforms, the projects include 24 Hours of Flickr, A Moment in Time, World Wide Moment, and One Day on Earth, to name but a few. One of the most celebrated and high-profile efforts at capturing crowdsourced digital media content in a 24-hour period is the blockbusting 2011 Life in a Day feature film, directed by Kevin Macdonald, produced by Ridley Scott and sponsored by YouTube and National Geographic, which asked for moving image submissions taken on 24 July 2010. On 15 May 2012, A Day in the World attempted a similar project on a similar global scale for photography.

These projects are united by their use of huge photographic volumes. In this aspect, at least, they parallel the arts practitioners who curate works from a mass of photographic fragments. They are all also concerned with numerical quantity and each also uses superlative language. A Day in the World, for example, boasted that more than 60,000 people in 190 countries participated and 100,000 pictures were submitted. As organisers described it, “the initiative became the most comprehensive documentation of a single day in human history through digital photography”. The accompanying exhibition, shown on 85,000 digital displays in cities across 22 countries, was billed as “the largest global photography exhibition ever staged”. The estimated worldwide audience for these was 46 million (Anon., 2012b: n.p.). The superlatives continued with the web resources for submissions being described as the “biggest searchable online picture archive of its type” (Anon., 2012a: n.p.).Massed numbers here confer reach, substance, authority; meaning rather than meaninglessness. A Day in the World was, additionally, based on compassionate and community-building aims; it was designed from scratch to create a meaningful experience. From Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s foreword to the book, to the opening of the exhibition by the Deputy Secretary-General of the UN, the potential of the project as a global force for peace and understanding was emphasised. For Tutu, a member of A Day in the World’s Global Advisory Committee, the proliferation of images in mass media, and the fact that “cameras are everywhere” intensified the requirement for such a collective endeavour (11-12).

Another aspect that these mass photography projects share — apart from their huge scale and their perhaps naïve faith in the power of networked technologies to unite the world — is also their sense of novelty. Like their more dystopian post-photographic art world cousins, each revels in its newness. Mass photography projects are framed as technological innovations and as responses to an apparently unique and pressing impulse to communicate collectively brought by new media forms in the age of Web 2.0. The role of the internet as so-called participatory media has been the driving force for many collective projects. As the producers of Life in A Day claimed: “The idea that you can ask thousands, tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of people all to contribute to a project and all to communicate about it and learn about it at the same time belongs essentially to this age that we live in. Life in a Day couldn’t have existed 100 years ago, 20 years ago, even 6 years ago.” (Anon., 2011: n.p.)

Massification historically: continuities and complexities

The way that digital technologies appear to have fundamentally altered mass photographic practice, in terms of photographic access, multiplicity and ubiquity, their ease of capture, circulation, sharing, and disposal, has been the subject of significant scholarly enquiry. Much of this literature has trumpeted the changes as epochal. Mass photography projects absolutely use this revolutionary rhetoric. Yet despite the grand claims made of photography’s death and rebirth, there is an emerging consensus that some of the early excitement about digital technology’s transformative effects on traditional media was somewhat overstated, and several critics argue persuasively that, in terms of popular photography practice, amplification and intensification is rather more prevalent than rupture (see, for example, Hand). Gillian Rose has argued that “the differences that digital technologies make is not so obvious” on practices that support social relations, such as the maintenance of familial networks. She argues, in this context, that “digital photography has not so much altered family photography as enhanced it” (82-3).While it is tempting to follow the claims of their creators and promoters and read digital mass photography projects as “cutting-edge exercise[s] that would be unthinkable without digital cameras and the internet” (Darke: 69), such projects may be more accurately read as continuations or reanimations of longer-standing photographic hopes and fears.

Let us remember that mass photography — in terms of access and scale — has been around for some time and is not a 21st-century phenomenon. Concerns about indiscriminate photography by amateurs leading to an image-saturated world have occurred regularly since the late 19th century and have continued with vigour throughout the twentieth (for similar fears in different geographies, see Coe and Gates; Lugon; McCauley). A significant difference is that now image-sharing platforms make the quantities visible. Previously, unless perhaps one worked in photo processing or was on the receiving end of submissions to a competition, there were few accessible means to view popular photography’s mass scale.

The final section of this article focuses on a historical project that shares something of the sense of scale with current mass photographic projects and even the “catalogue aesthetic” of post-photographic artists who play with volumes. The One Day for Life photography event, nearly 30 years ago, had ambitions to be the biggest photographic event the world had ever seen. Via a large-scale national press campaign, “everyone with a camera” was invited to take a photograph of everyday life in Britain on 14 August 1987, to compete for a place in a commemorative book and to raise money for charity, as each submission was to be accompanied by a pound entry fee. With no particular prescription as to subject matter or style, the resulting 55,000 submissions form a large-scale and largely unsorted mass, which is preserved at the Mass Observation Archive at The Keep repository in Sussex, UK. At first glance they appear to offer a tantalising, rarely-available cross-section of analogue popular photographic practice on one randomly selected day. In an analytic manoeuvre of reverse engineering, however, I would like to suggest that the photographs — which could be described as a 1987 version of Kessels’s 24 Hrs in Photos — may also offer a way into understanding newer mass forms. Certainly, from examining them closely, I would argue that the methods needed to interpret them are not hugely different to those we need to apply to understanding mass photography in a 21st-century context.

The word ‘context’ is key. Having looked at every single photograph in the archive, I can confirm that the One Day for Life collection is indeed overflowing with hundreds if not thousands of images of dinners, pets, babies, and sunsets — to offer just a few examples of the subject categories that are frequently used as synonyms for the apparently repetitive, sentimental, clichéd, and inconsequential imagery of the popular photograph on the internet (Pollen, 2013). Before we conclude, however, that this snapshot of mass photographic practice confirms that the amateur photographer ever was unimaginative and her or his practice is therefore redundant, as some scholars have done (Stallabrass; Slater), we always need to ask what purpose such images serve. Much as it might be tempting to see this collection as an index of mass practice, and thus draw conclusions – perhaps damning as to skill and imagination when the blurred or wobbly qualities of many photographs are considered; perhaps more optimistically in terms of participation and communication if the celebratory mode is preferred — these photographs were produced under particular conditions, as all photographs are. In the context of One Day for Life, each photographer made a public statement through his or her photograph, and each aimed to fulfil a brief, variously to depict everyday life, to offer a portrait of Britain, to raise money for cancer charities, or to compete for a place in a book. Each photograph within the mass necessarily has its own story, which I worked hard to find, a quarter of a century on, as most originally came in without any accompanying documentation.

What my chosen research method — talking to people in detail about their photographs and their purpose for participation — revealed most of all is that the meaning of the image can offer a counternarrative to that which one grasps when looking at image content alone; the reason the photograph was made and the meaning it had for its maker often exceeded or subverted the image that carried it. The idiosyncratic narratives that emerged from first-hand accounts show that the surface image of the photograph is at times tangential to, or even fully contradictory of, its ulterior function. Those photographs that seem most banal and ordinary could, and often did, carry much more complex statements of intent.

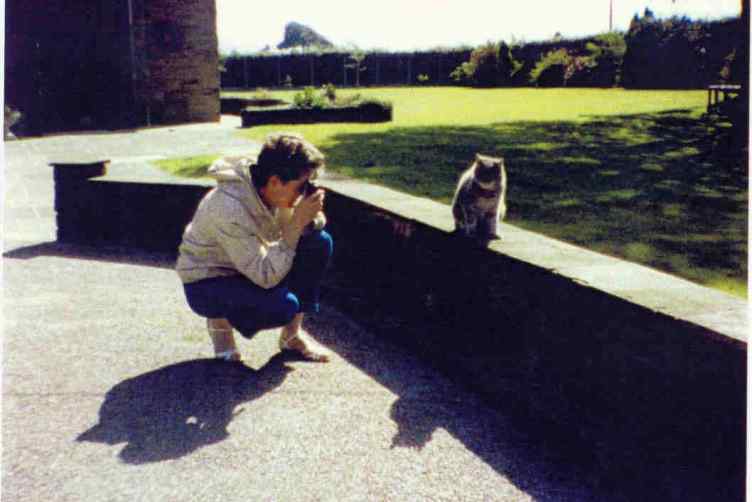

For reasons of space, I will just offer a brief example here. From the 55,000 archival prints, I have selected a single photograph of a kitten, in part because the photography of cats has come to stand in for a particular kind of sentimentality and banality in the age of the internet. Seen through a dystopic post-photographic frame, the popularity of images of cats online is sometimes used to signal the lowest common denominator of internet communication, and the limitations of imagination in the face of infinite possibility. The online cat photograph has come to form such a metonymic relationship with the expansion of digital and networked imagery that it has recently been the subject of academic and curatorial scrutiny (see, for example, the 2012 exhibition For the LOL of Cats at London’s Photographer’s Gallery, and the 2015 exhibition How Cats Took Over the Internet at the Museum of the Moving Image, New York). In addition to these more scholarly appraisals, there is a wealth of popular publications (see one example here) that playfully claim the cat to be the unofficial mascot of the internet, and that attempt to calculate the proportion of internet traffic dedicated to cats (estimates range from a modest 0.25% to an unlikely 15%). Among the 55,000 photographs of the One Day for Life archive, there is also an abundance of pet photographs. Dogs, budgies, hamsters, and more are pictured, often playfully. Cats of all kinds are photographed from all angles, in a wide range of settings; in a form of meta-commentary there are even photographs of cats being photographed.

Stella Skingle was one of the participants to submit a cat photograph. As revealed in interview, she was an example of a participant who was typical of many other entrants in that she never entered photography competitions and had not taken part in a public photography activity before. She had little interest in developing a serious photographic practice and tended to only use her simple push-button camera for family events. The cancer fundraising aspect of the project alone had attracted her to take part and she submitted several photographs of her teenage daughter, who in 1987 was recovering from chemotherapy treatment for leukaemia where she had lost her hair. Skingle also submitted a photograph of the new kitten that she had given her daughter to provide some comfort during her illness. This was the photograph that was selected for inclusion in the final publication by the book’s editors for reasons of the creature’s visual appeal alone, and nothing of this purpose was visible in the resulting image or even in its caption (Search 88: 296). For Skingle, however, the kitten photograph was necessarily deeply enmeshed in a family’s experience of cancer; it was more than a cute picture to sell a coffee table book. It was certainly not a visual cliché.

The 130 participants I contacted had many and various passionate, personal, and sometimes political reasons for taking their photograph. They submitted photographs of kittens, sunsets, vases of flowers, and thatched cottages in droves, but used the available means of a popular image repertoire to communicate their particular and distinctive individual messages. What the photograph was for, and what it was expected to do, shaped its meaning beyond its subject content. Skingle’s kitten is an idiosyncratic example, but there is no reason to assume that the other amateur cat photographs in the archive are merely pictorial clichés and collectively constitute visual noise; each has a unique meaning to its maker. By the same token, there is also no reason to assume that other amateur photographs, en masse, are pictorial clichés and visual noise; no matter how many there are, each has a unique meaning to its maker.

Conclusion

To close my article, I offer some methodological reflections on the conceptualisation and interpretation of mass photography, on either side of the post-photographic moment, or whatever we would like to call the cultural and technological shift that has enabled the proliferation of large new volumes of photographs. As my brief example has shown, once personal stories become attached to photographs they become troublesome material from which to extrapolate generalisable meaning about the mass image. Photographic theorist Scott McQuire has observed something similar, noting: “Beyond a certain point, the irreducible specificity of each image asserts itself, stubbornly refusing to surrender to the demands of the ‘example’.” (141.)This is particularly the case the more is known of a photograph’s back story. My larger research project (2016), only touched on briefly here, drew out the specificity of singular photographs from their mass frame. This necessarily removed them from a narrative of universalising equivalence and disrupted their capacity to function smoothly as part of an aggregate. Roland Barthes has also observed that “Photography cannot signify (aim at generality) except by assuming a mask” (34).In order to carry a larger narrative, then, a particular, grounded photograph can only come to stand for photography as an abstract concept through the sacrifice of its particular conditions.

There is a longstanding tradition for positioning the amateur photographer as unthinking (Stallabrass; Slater), which has expanded in popular press accusations about digital photographs online in the present day. Each photograph, however, is always produced for a purpose, and its surface image content may run counter to what it means. In case of popular photography, the resulting images can only become examples of, say, banality or unity, when they are gathered together in volumes and types and their singular stories suppressed. Mass photography – now ever more visible, now performed ever more publicly, now larger than ever before – is neither inherently indicative of meaningless visual chatter or of democratic communication. Only when blurred into a macro view can it be made to stand in for cultural anxieties and desires. By disaggregating masses, we are left with individual experiences and individual stories far removed from Ritchin’s “undifferentiated content”, which is only seen from a distance. The conceptualisation of mass photography as a blinding plethora of sameness or as vision of humanist equivalence ignores the individual complexities of the single images that any mass form comprises, past or present.

By looking to historic examples of mass practice we can help moderate superlative claims and allay apocalyptic fears of what is often claimed to be something entirely new and uniquely overwhelming. Further, if we apply a microhistorical method to the photographic macro, we can access the particular, grounded, and granular conditions that underpin each and every act of image-making. Grand overviews of photographic masses tend to lead to generalisation and also to dizziness. As Fontcuberta has noted of his post-photographic condition, “never before have we benefitted from such an exuberance of repositories” but he then opines, “we tend to lose our way in the inextricable jungle” (12).To continue his metaphor, it may be the case that those looking at the woods are not seeing the trees.

Studies of new massification confirm that continuities of practice are evident in what people take photographs of and what they say about them. Images of friends, families, pets, and personally significant objects and places continue to represent the cornerstone of what people value and what people picture. These practices endure in spite of rather than because of their new media forms; they are not wholly determined by the technology that brings them into being. To emphasise artificial conceptual ruptures between older and newer forms is to ignore a rich continuity that may be less headline-grabbing than the rhetoric of revolution but is more representative of practice. Perhaps there is not as much difference as there first seemed between photography and post-photography after all. There’s no need to grieve.